Caring for the Land

Green Fields Farm Returns to the Good Life

By Stacy Moser | Photography by Justin Borja

“We’re raising pigs and cattle the way that God intended,” John Brasher declares from the driver’s seat of his pickup truck as he bumps down a dirt road that accesses the pastures of Green Fields Farm.

“Our concept here is to mimic Mother Nature.” He stops the truck and jumps out onto the soft dirt of the road. He steps over a low wire fence surrounding a quarter-acre of land as a small herd of rusty-colored pigs eyes him curiously. He points to some round divots in the soil of the pasture, explaining that this is where pigs root around with their snouts, searching for tasty bugs and the roots of plants. “When they do that, it’s great for the soil,” John says, squatting to scoop up and examine a handful of deep-brown dirt, which he says is rich in nutrients.

The Brashers, John and his wife, Jennifer, are a new breed of farmer—employing low-tech, environmentally focused strategies to accomplish a simple goal: create healthy soil in order to grow healthy food.

Jennifer’s parents, Leonard and Inez Cobb, have spent their entire married life on that property, Leonard’s parents having farmed the land since before he was born. As time went on, farming methods followed in the footsteps of most industrialized farms across America in the last century. They became efficient machines, using chemicals to replace depleted nutrients in the soil and kill pests and large machinery to accomplish what had been done by hand (and by mule) in days past.

The family describes their loss of enthusiasm about conventional farming methods they’d used to grow cotton and corn in the past. “The combination of high costs and more and more extreme weather-related crop failures made us realize that the cycle was broken. The soil wasn’t working properly. It wasn’t sustainable,” says Jonathan, Jennifer’s younger brother.

But then, on one prophetic day, Jonathan and Leonard attended a lecture about healthy soils.

Soil scientist Ray Archuleta had traveled to Temple to offer a seminar educating family farmers on techniques to heal the soil, creating healthy habitats, improving food quality and strengthening a farm’s business overall. Jonathan and Leonard were fascinated with the concept.

The family began to research the connection between nutrients in the soil and nutrients in food they ate and their overall health. “We thought, ‘What if we raise our own cattle, got chickens for eggs, cows for milk and pigs for pork? We could control how we feed them and how they’re treated. Then we could find like-minded families who would want to buy from a local farm where they can visit and see how the animals are raised,’” Jennifer says.

“What we do is called regenerative agriculture,” she continues. “It goes beyond organic or sustainable farming. We heal the land through management practices. We don’t till the soil, we plant cover crops, reestablish native prairie grasses and change the animals’ impact as they move across the land. We use rotational grazing. The animals graze in one area, then we move them to another. By the time we get back, the grasses have sprung right back up since they weren’t over-grazed.”

The family was determined to farm in a humane way, too. “We treat the animals kindly and we have respect for them,” John says, as he surveys the cattle grazing in the pasture.

“Moving the animals is so important,” he explains. “If you don’t, they congregate in one area all the time. Then parasites congregate there too. So if we move the animals constantly, we don’t have to give them antibiotics or wormers. The parasites are gone because they have no host.”

Most cows are raised on grass until they’re about a year old. Jennifer describes what usually happens next. “Then, unfortunately, conventional farms ship them to a feedlot and fatten them on grains very quickly. That’s so they weigh more and can be sold for more.”

“It’s not good for the animal—their systems aren’t built for that,” John says, shaking his head. “It’s harder to get a steer fatter on grass. But to that we say, ‘So what?’ It’s worth doing.”

“We have 450 acres of land here,” Jennifer waves her arm at the horizon. “There’s a wooded forest with native elms and Virginia rye grass. We also planted diverse cover crops for the animals to eat in the pastures.”

John laughs. “When I open the gate and let the steers in a new area, they’re like a kid in a candy store. They kick their legs up and run to the new grass!”

“It’s the same way with pigs,” Leonard adds. “They forage for clovers and grasses and it comes across in the flavor of their meat—it’s a little darker than the pale meat you see in the store. And after they’ve stayed in an area for about a week, this land is fertilized and it didn’t cost us a dime to do it.”

Jennifer describes the role her parents play on the farm. “For two retired people, they aren’t very retired!” she laughs. “They work every day with us, which is nice. In order for this to work, it takes all of us—a village.” Jonathan and his wife, Kaylyn, regeneratively raise sheep on the farm, too.

Leonard recalls the first time he realized that the new methods were definitely improving the farm’s soil. “It was a blazing hot August afternoon—103 degrees out. I took an infrared thermometer and went out to our neighbor’s field—he had plowed and plowed until there was nothing left. The thermometer said his soil was 155 degrees. Nothing can live in that hot soil! Our soil’s temperature was 88 degrees. The matt of plant matter was holding in moisture.

Plant roots are like a wick that brings moisture to the surface. It has a cooling effect. That’s when I knew we were on to something positive,” he says, smiling.

Inez says she’s delighted at the changes taking place at Green Fields Farm. “Our soil is healthy, so the plants are healthier—and pests aren’t interested in healthy plants. The capacity of soil to hold water is higher and the plants can go longer without rain.”

She recalls times when the farm struggled. “We were discouraged with what modern farming had become. When Leonard and I were first married, our kids could play in the dirt. Then, in the ’80s, all these harmful chemicals came out. I wouldn’t dare let my kids play in the dirt any more. You didn’t know your land. You weren’t a part of it. I couldn’t lie in the field in the sunshine any more. Now, I can feel that energy coming back to the soil. All this work has been so worth it.”

She leans forward, saying quietly, “I hear people say that you can’t go backward. Well, I’m thinking, yes, you can go backward—back to a better way of doing things. The good life.”

GFFTexas.com | HolisticManagement.org

The Advantages of Buying in Bulk

The Advantages of Buying in Bulk

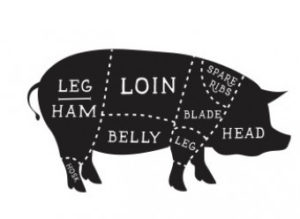

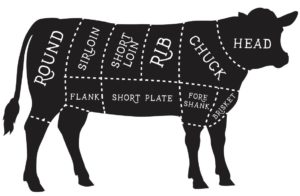

“Our passion is the desire to know where our food comes from,” John says. “We want ours to be the best and share that with people who are like-minded.” Green Fields sells frozen beef and pork in whole, half and 25-pound “bundle” boxes, each containing most major cuts—sirloins, rib eyes, tenderloins, cutlets, etc. When it comes to menu planning for the week, buying in bulk and having beef and pork already in the freezer is a big time saver. Consider this:

A typical upright freezer has a capacity of about 20.7 cubic feet. A typical family of four:

• Consumes about half a beef in one year, requiring about 10 cubic feet in the freezer.

• Consumes a whole pork in one year, requiring about 5 cubic feet in the freezer.

Jennifer Brasher knows just how to showcase the delicious meat that Green Fields Farm produces. “This roast pairs well with sweet potatoes and Brussels sprouts.”

Jennifer Brasher knows just how to showcase the delicious meat that Green Fields Farm produces. “This roast pairs well with sweet potatoes and Brussels sprouts.”

Easy Herb-Crusted Pork Roast

4- to 5-pound pork shoulder or Boston butt roast

10 garlic cloves, smashed and chopped

4 tsp. chopped fresh rosemary

4 tsp. chopped fresh thyme

4 tsp. whole-grain mustard

1/4 cup plus 2 Tbsp. olive oil

In a bowl, combine garlic, rosemary, thyme, mustard and olive oil. Coat the roast with the marinade. Cover and refrigerate for at least 6 hours or overnight. When you’re ready to cook, preheat oven to 300°. Place roast in a roasting pan and bring to room temperature. Cook roast, covered. Check after 2 hours and then every 25 minutes until thermometer inserted in the center registers 175° (for medium). Transfer to baking sheet. Turn oven up to 400°. Bake an additional 13–17 minutes uncovered.