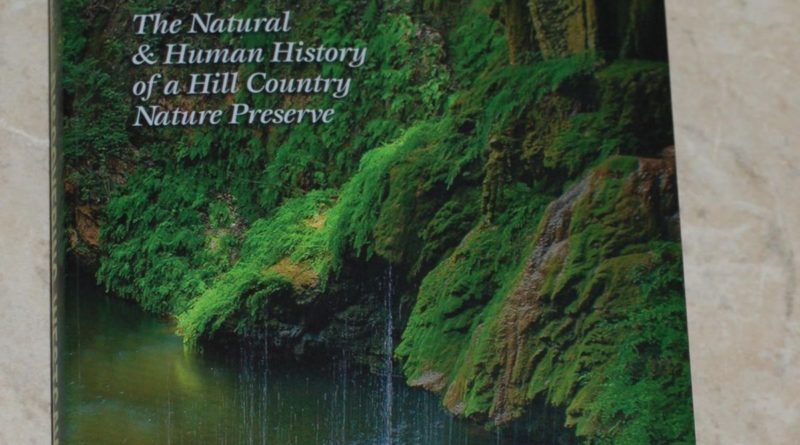

‘Discovering Westcave’ guides visitors through preserve

“Discovering Westcave,” by S. Christopher Caran and Elaine Davenport, published by Texas A&M University Press 2016, is not your typical guidebook, one that merely points out the native flora and fauna of a particular place or region. But it’s not merely a coffee table book either; chock full of glossy color photos and little else. Discovering Westcave is one part love letter to a place and the people who lived there, going back several thousand years; one part geology and biology examples in context to how Westcave evolved; and one part, for you avid wildlife biologists, illustrations of classification tables and identifications of the species found there.

In the book’s preface, Westcave CEO and executive director Molly Stevens sets the tone with a profound argument for introducing young children to wild places such as Westcave. “During the last two decades, childhood has moved indoors. With the average American boy or girl spending an average of eight hours a day in front of electronic screens, there is an increasing divide between children and nature. That divide is linked to some of our most disturbing childhood trends, such as the rise in obesity, attention disorders and depression.”

The book is organized into three sections.

Part one is a visitor’s guide. First you will take a virtual walk through the preserve. Through illustrations and photographs and vivid explanations, the authors will introduce you to the birds and butterflies, grasses and wildflowers, boulders and bedrock that you would see. Next, step inside the visitors’ center where exhibits such as the solar observatory and sky map connect the earth, sky and stars. Clearly, the authors have an emotional attachment to Westcave.

“Footprints fade away, as do echoes of laughter, curious inquiries, and expressions of awe,” Caran and Davenport wrote. “What remains is an invisible armor, fashioned from a common resolve that the preserve must forever be what it is today: a constant place of exquisite perfection, but always displaying something new.”

Part Two, The Place, delves into the geography and how Westcave’s location in “flash flood alley” has affected its evolution. Readers will also learn how the preserve changes through the seasons. And even if you’re not a rock hound, the diagrams and explanations of the geology are easy to grasp and help illuminate how the canyon and springs, streams and caves evolved.

Part Three, The People introduces us to an endearing cast of homesteaders, Mormons, mill operators, artists, educators and conservationists who have lived on or near, or visited Westcave. Here you will find memories of encounters with snakes and panthers, flash floods and blessed isolation. During the 1970s, Westcave was known as a cool hangout for Austin musicians such as five-time Grammy Award nominee Marcia Ball. “Those beautiful spots, in a wet spring, were amazing to me and a big part of why we stayed in Austin,” Ball writes in an essay. “Westcave was one of those special places.”

The poignant story by Amber Gosselin, “Growing up at Westcave Preserve,” captures the magic and allure Westcave has had on generations — speargrass battles with her brother; swinging on a rope and dropping into the Pedernales, sleeping with the hum of a box fan perched in a window — Gosselin paints a picture of an idyllic childhood.

And a whole chapter is dedicated to her late father, John Ahrns, resident caretaker, naturalist and educator at Westcave from 1974-2010.

If you visit Westcave, this is a worthy read because you will uncover more information than can be digested in a single visit. But even if you don’t visit, or have a visit on your bucket list, Discovering Westcave is time well spent because it will carry you away to a unique and peaceful Texas respite, one that is a shining example of how important conservation is in the burgeoning Central Texas corridor.