Iconic modern dancer Alvin Ailey hailed from Rogers

By Janna Zepp | Public domain photos

Rogers, the birthplace of one of the most internationally famous dancers and choreographers in the world, sits less than 15 miles southeast of Temple. From a town of only 1,200 or so people rose an iconic performer whose work changed and shaped the course of American modern dance for generations to come. Alvin Ailey was a Central Texan, and one Central Texas is proud to remember.

Rogers, the birthplace of one of the most internationally famous dancers and choreographers in the world, sits less than 15 miles southeast of Temple. From a town of only 1,200 or so people rose an iconic performer whose work changed and shaped the course of American modern dance for generations to come. Alvin Ailey was a Central Texan, and one Central Texas is proud to remember.

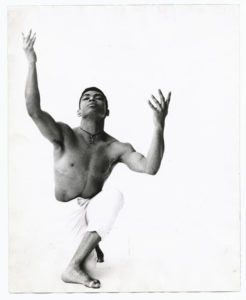

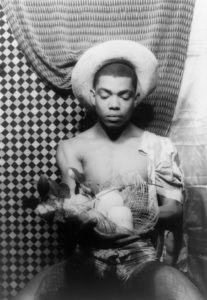

Born to a mother in her teens on Jan. 5, 1931, in Rogers, Texas, Ailey became one of the leading figures in 20th-century modern dance. Abandoned by his father when he was still a baby, he grew up poor in the small Texas town of Navasota. During his childhood, Ailey drew inspiration from the Black church services he attended as well as the music he heard at the local dance hall. His mother, Lula Cliff Ailey, worked as a farmhand and as a housemaid to support them both. They moved frequently, chasing stable, long-term employment for Lula.

They left Texas for California when Ailey was 12. Lula found work; Ailey enrolled in school and eventually attended the University of California-Los Angeles. In Los Angeles, Ailey excelled at languages and athletics. After seeing the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo perform, Ailey fell in love with dancing. He studied modern dance with Lester Horton in 1949. He joined Horton’s multicultural dance company the following year. When Horton died in 1953, Ailey took over as director. The following year, Ailey made his Broadway debut in Truman Capote’s short-lived musical House of Flowers. He appeared in The Carefree Tree in 1955. Ailey served as the lead dancer in another Broadway musical, Jamaica, starring Lena Horne and Ricardo Montalban in 1957. While in New York, Ailey also studied dance with Martha Graham and acting with Stella Adler.

Ailey achieved his greatest fame with the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater (AAADT), the dance company he founded in 1958. Both his works, Blues Suite and Revelations drew inspiration from the blues, spirituals and gospel songs of his youth, as well as Ailey’s deeply ingrained memories of his childhood in rural Central Texas and the Baptist Church.

“From his roots as a slave, the American Negro — sometimes sorrowing, sometimes jubilant but always hopeful — has touched, illuminated, and influenced the most remote preserves of world civilization,” said Ailey. “I and my dance theater celebrate this trembling beauty.”

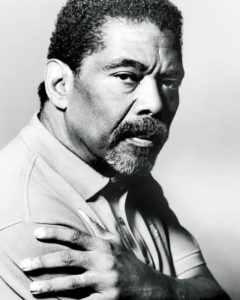

In the 1960s, Ailey took his company on the road. The U.S. State Department sponsored his tour, which helped create his international reputation. He retired from dancing in 1965, but he continued to choreograph many masterpieces. Ailey’s Masakela Language, which probed the experience of being Black in South Africa, premiered in 1969. He also formed the Alvin Ailey American Dance Center — now called the Ailey School — that same year.

In the 1960s, Ailey took his company on the road. The U.S. State Department sponsored his tour, which helped create his international reputation. He retired from dancing in 1965, but he continued to choreograph many masterpieces. Ailey’s Masakela Language, which probed the experience of being Black in South Africa, premiered in 1969. He also formed the Alvin Ailey American Dance Center — now called the Ailey School — that same year.

“I’m interested in putting something on stage that will have a very wide appeal without being condescending; that will reach an audience and make it part of the dance; that will get everybody in the theater,” Ailey said about his original productions.

In 1974, Ailey used the music of Duke Ellington as the backdrop for Night Creature and expanded his dance company by establishing a junior company, the Alvin Ailey Repertory Ensemble. In all, Ailey choreographed close to 80 ballets during his choreography career.

For all of Ailey’s contributions and accomplishments, his work also received its share of criticism and racism. Often, AAADT found itself pigeon-holed as an “ethnic” dance troupe rather than a modern American dance company. The AAADT included other ethnicities along with Black dancers, drawing complaints that the company was not “Black enough.” Ailey himself was subject to discrimination because of his sexual orientation as well as the color of his skin.

“If you live in the elite world of dance, you find yourself in a world rife with racism. Let’s face it,” Ailey said in a discussion on bigotry. “Racism tears down your insides so that no matter what you achieve, you’re not quite up to snuff.”

But Ailey was more than “up to snuff,” and the world knew it. In 1988 near the end of his life, Ailey was honored by the Kennedy Center for his contributions to the arts. Ailey died on Dec. 1, 1989, at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City from terminal blood dyscrasia, a rare disorder that affects the bone marrow and red blood cells. It was later revealed that Ailey had died of AIDS. He was only 58 years old.

Professional dancers grieved for Ailey at his passing. Dancer Mikhail Baryshnikov described Ailey as having a big heart and a tremendous love of the dance and that his work made an important contribution to American culture.

Even posthumously, Ailey remains an important figure in the arts through the ballets he created and the organizations he founded. The dancers with the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater have performed live for more than 20 million people around the world and countless others have seen their work through many television broadcasts.

Even posthumously, Ailey remains an important figure in the arts through the ballets he created and the organizations he founded. The dancers with the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater have performed live for more than 20 million people around the world and countless others have seen their work through many television broadcasts.

Rogers recognized Ailey as a hometown hero in 1993 by renaming a street in his honor, and the Bell County Museum in Belton has a permanent exhibit about him, opened in 1996. In 2016, Ailey was remembered in Rogers with the unveiling of an historical marker from the Texas Historical Commission at the Rogers Civic Center near Alvin Ailey Boulevard.

“I am trying to show the world that we are all human beings and that color is not important. What is important is the quality of our work,” said Ailey, when asked about what he found important about dance. “Dance is for everybody. I believe that the dance came from the people and that it should always be delivered back to the people.”