Oveta Culp Hobby: A Central Texas woman of integrity

By Janna Zepp | Public domain photos

Oveta Culp was only about 6 years old in 1911 when the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union visited Killeen, and at Sunday school all the children were invited to sign the pledge never to drink liquor and receive a WCTU white ribbon to wear. Culp considered signing and decided against it. It was not that she wanted to drink alcohol, but that she might wish to try it when she was an adult. She thought the responsible choice meant not giving her word in oath unless she was fully prepared to keep it. It was an exceptionally wise, if not shocking, answer for a child that young. It would have been easier to sign the pledge and then forget all about it later in life, but Culp placed deep value on her integrity. It would be a mark of her character and a cornerstone of her reputation in everything she did for the rest of her life.

Born in Killeen, the second of seven children to Ike Culp, a lawyer and Texas legislator, and Emma Hoover Culp, a suffragette who encouraged her daughter to stand up for women’s rights, Oveta Culp loved horses, studying law and government.

Culp attended Bell County schools, graduating from Temple High School in the top tier of her class. She studied at Mary Hardin Baylor College in Belton, taught elocution, put on school plays, and was a reporter at the Austin Statesman. At 20, she was asked by the speaker of the Texas House of Representatives to act as legislative parliamentarian. She served in that role until 1931, while attending classes at the University of Texas. She became a clerk of the State Banking Commission and codified the banking laws of the state of Texas. Later she became a clerk in the legislature’s judiciary committee.

It was during Culp’s burgeoning political career that, in 1931, she married her father’s friend, former Gov. William Pettus Hobby. The couple had two children, one of which was William P. “Bill” Hobby Jr., who served a record 18 years as the 37th lieutenant governor of Texas.

Culp Hobby worked in the publishing world on her husband’s newspaper The Post in Houston. She held several positions within the paper including book editor. In 1937, she wrote and published a book, Mr. Chairman, about her activities at the Texas Legislature.

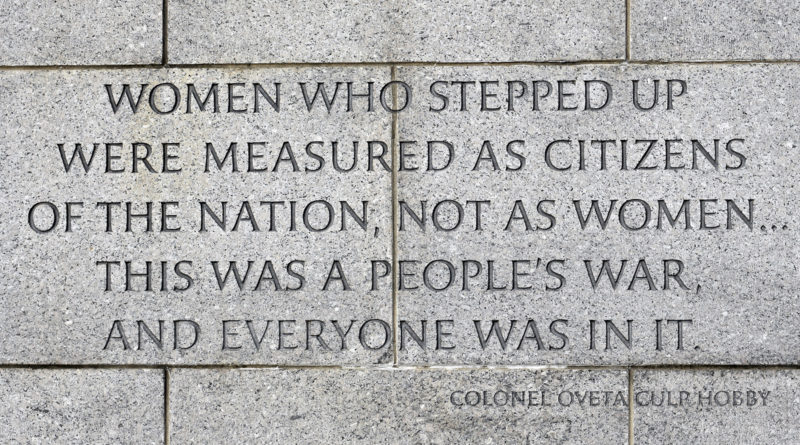

World War II changed Hobby’s life. From 1941 to 1942, she served as the head of the Women’s Interest Section in the War Department Bureau of Public Relations. In this role, she looked for ways in which women could serve their country and laid the groundwork for them to do so by the time that the United States entered the war. Congress passed a bill which created the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps in May 1942 and Culp Hobby became its first director. In 1943, she earned the rank of colonel, when the WAAC integrated into the United States Army, becoming the Women’s Army Corps.

In the WAC, women were taught various skills needed to serve in the military. Initially, expectations were low. It was thought that three women would be needed to fill on man’s non-combat job. It turned out that women were highly efficient and competent workers, thus overcoming the manpower shortage on the battlefield. But their work initially was not compensated.

On the first payday, the women doctors were denied their salary. They were told that only men serving as doctors were authorized to receive pay and “women were not doctors.” Culp Hobby stood up to Congress, demanding that her personnel be paid. When she learned that women were being dishonorably discharged for pregnancy without permission, she argued that the fathers of the illegitimate children receive dishonorable discharge as well. Her perseverance paid off: regulations for women in all branches of military service were changed, and pregnant women became entitled to honorable discharge and medical care.

Despite the success of the WAC, opposing views still existed, but Culp Hobby used her media talents and promoted the WAC as a space where women could safely learn vocational skills and contribute to the war effort. By 1944, more than 600,000 WACs were asked to serve all over the world.

Culp Hobby remained the director of the WAC throughout the war. For her dedication and effective supervision of the WAC, Culp Hobby was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for outstanding service by the U.S. Army in January 1945. She was the first woman in the Army to receive this award, which was the highest non-combat award given by the military at that time.

Culp Hobby resigned from the WAC in July 1945 and returned to The Post as its executive vice president. She maintained her interest in politics and actively supported Republican candidate Dwight D. Eisenhower’s presidential campaign.

One of Eisenhower’s first acts as president in 1953 included creating the Department of Health, Education and Welfare and naming Culp Hobby as the first secretary of the new department. There, she worked on matters related to health, education and educational funding. She also helped plan for the first distribution of the newly created polio vaccination in the United States in 1955, after which she stepped down from the office. It was then that she returned to work in media and public service.

Under Culp Hobby’s direction, the Post supported Houston’s growing Black community by reporting on topics important to them and telling their stories in a positive way. As a businesswoman, she promoted equal employment by hiring women and minorities as reporters and journalists. One notable example is when a struggling law school graduate showed up on the steps of Culp Hobby’s television station at a time when most major Houston law firms were not hiring women. Excited about showcasing Houston’s first female news reporter, she took a stand on hiring Kay Bailey Hutchison who later went on to become Texas’ first female U.S. Senator.

A media and military legend, Oveta Culp Hobby was a woman who stood up for equal opportunity and women’s rights. After her death at the age of 90 in 1995, she was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame with a citation that reads: “You were respectful of the power you wielded in influential positions. You made the road smoother for the women who followed you.”