Sisters of Sanctification: Shelter, service and salvation from violence in the 19th century

By Janna Zepp | Public domain photos

Belton might well be the site of the first women’s shelter in American history. Bell County divorce records from the 19th century bear out the evidence of its existence in detail. The women seeking divorces were members of the Belton Woman’s Commonwealth, also called the Belton Sanctificationists or Sisters of Sanctification. It was a women’s commune that began formation in the late 1860s by Martha McWhirter and her women’s Bible study group.

Over time, an alternative communal life evolved out of the group, replacing the women’s marriages and family situations. By the 1870s, religious separatism of the Sanctificationist women provided a sheltered environment for the development of some unconventional religious practices. The women believed they received prophetic dreams and direct revelations from God. The “sanctified” must separate themselves from the “undevout.” Sanctified wives could still live in their marital homes and perform their household duties, but with no sexual and as little social contact as possible with their unsanctified spouses.

The physical and emotional abuse of the women was bluntly evident in several divorce cases involving the Sanctified Sisters. Ada McWhirter Haymond, McWhirter’s daughter, testified that her husband, Ben, kept the family in a state of chaos. She said that they disagreed over family finances, and that he tried to forcibly throw Ada out of their home. He finally left her and their children. McWhirter herself testified at her daughter’s divorce trial, saying that “there is no sense in a woman obeying a drunken husband.”

Other women detailed the abuse they suffered before they joined the Sanctificationists. Margaret Henry’s husband was cruel to her whether he was drunk or sober. Agatha Pratt’s husband was almost always drunk and often abused her. Josephine Rancier’s husband deserted the family, but not before abusing them physically and financially.

About 50 known members, including at least one African American woman thought to be a former slave, counted themselves as “sisters.” Some women, worried about the future of their daughters or sisters, joined the community with their female relatives. The span of ages of the commune members certainly deserves notice. Many of the second-generation daughters remained in the community and never married. If they did not stay, they often kept in touch with the commune. Belton mothers and daughters joined the Sanctified Sisters as a way out of a cycle of abuse. Mothers gave up their individual responsibilities for their children, but all the women believed child rearing was a community task. The Sisters maintained a school for children in the community. They ran a farm, sold eggs and milk, and cut cedar wood in the area to earn money.

In the 1880s, the residents of Belton blamed the Sanctificationists for rising separation and divorce rates, and for undermining the meaning of marriage through their celibate lifestyle. When two immigrant Scottish brothers, Matthew and David Dow, joined the group for religious reasons they were kidnapped, whipped, warned to leave town, and briefly committed to the state asylum in Austin, but released when the hospital’s doctors deemed them sane. One sister was not as lucky.

In 1883, Sister Mary C. Johnson was tried and sent to the asylum in Austin. Upon the death of her husband, John, Johnson inherited his $2,000 life insurance policy from the Knights of Honor, one of the most successful fraternal beneficiary societies of its time. Johnson refused to take the policy because John had been “unsanctified.” Her reasoning: because she refused to take money from him when he was alive, she was not going to accept it after his death. Johnson’s brother then petitioned that she be tried for lunacy solely on the grounds of her refusal of the insurance money. A Bell County jury found her insane, and she was sent to the same asylum as the Dow brothers. Even though the charges of religious fanaticism against Johnson had been identical as those charged to the Dow brothers, the 19th Century asylum authorities believed that a woman like Johnson was a potential danger to the public. Johnson, they said, had acted in ways that did not conform to “normal ladylike behavior.”

The economic power and business acumen of the Sanctificationists eventually turned the tide of public opinion in their favor. The commune’s hotel and other business ventures had become successful by the late 1880s, and the Belton Woman’s Commonwealth became increasingly respected and accepted. In 1894, Martha McWhirter was elected as the first woman to serve on the Belton Board of Trade. The sisters’ book collection, housed in a small room in their hotel, became so popular that it was moved to a larger facility outside the commune, and in 1903 it formally became the city’s public library.

In 1899, the entire commune retired from farming and moved to Washington, D.C. where they opened boarding houses and a hotel, and participated in local feminist organizations. In 1903, there were 10 surviving members who bought a farm in rural Maryland to provide food for their city dining halls, and as a country retreat for themselves.

McWhirter died in 1904 and, with her passing, the community began to fade away. The last member of the commune, Martha Scheble, died in 1983 at the age of 101.

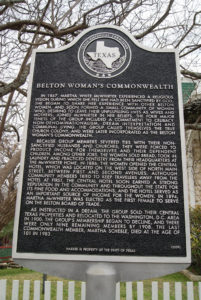

Signs of the Belton Woman’s Commonwealth remain. The George and Martha McWhirter House at 400 North Pearl St. in Belton is on the National Register of Historic Places. An historical marker dedicated to the Sanctificationists stands in front of the property, giving a brief history of the commune. The sisterhood, while not the beginning of the Women’s Rights Movement in the United States, was certainly a vital part of it right here in Central Texas.