A Schoolroom of Hope

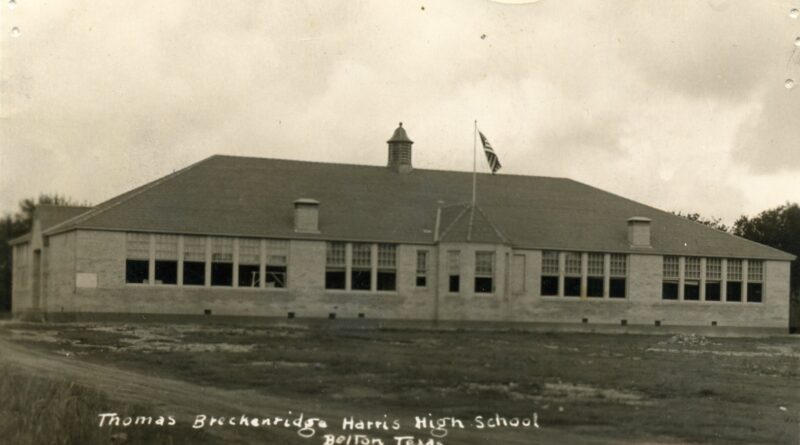

By PHOENIX CARLISLE | Photo courtesy of the BELL COUNTY MUSEUM

Editor’s Note: The following article was an essay written for the Barbara Jordan UIL Essay competition. Phoenix Carlisle was named the top speaker for the District 22-5A High School Academic Meet and will advance to the state competition. AP Style changes have been made, as well as some minor paragraph structuring.

“Now the training of men is a difficult and intricate task. Its technique is a matter for educational experts, but its object is for the vision of seers. If we make money the object of man-training, we shall develop money-makers but not necessarily men; if we make technical skill the object of education, we may possess artisans but not, in nature, men. Men we shall have only as we make manhood the object of the work of the schools — intelligence, broad sympathy, knowledge of the world that was and is, and of the relation of men to it — this is the curriculum of that Higher Education which must underlie true life.” Quote from W.E.B Du Bois’ The Talented Tenth.

Education is a complex art form. It requires patience and structure while demanding a fluid flow of knowledge. Knowledge that has been rewritten throughout time to teach the youth of the future what they may need to go out into the world as capable persons. Unfortunately, the concept of education is regarded in our modern American society as a requirement, something that everyone goes through although it may or may not stick with the individual student. There are moments when we have to appreciate this easily accessible concept because there were times in our own country’s history when this was not the truth for everyone. Decades where hundreds of black students were repeatedly told no to something as small yet impactful; an education. Almost every student will complain about the long hours of boring useless lectures and materials without realizing the privilege it is to be granted higher learning. The small student body of West Belton, later renamed T.B Harris, school understood the trials and tribulations of gaining an education as black students during a time of southern segregation.

Within Central Texas, the town of Belton, next to the west bank of Nolan Creek, stands the first African American school in the area. The three room building that taught all grade levels, only named “Colored School,” stood proudly for the first time in 1882 with its one teacher, Mrs. Aleck McGee, who would teach for $35 per month. The next teacher introduced to the enrichment of these students was Professor Thomas B. Harris (1862-1907), who began teaching the high school students in 1890 until his death in 1907. He was a well loved teacher and principal who would be honored for his early contributions to the foundation of the schooling. Luckily by 1900, the school was renamed to “West Belton,” still segregated yet not singled out.

Then began the fires. There were three reported fires during the history of the institution that would completely ruin the buildings yet would lead to an improvement in structure and the enrichment of the student body. If you deep dive into the history, there will be no report of what caused any of the fires, just a year and statement. Reported facts, a blank statement rather than what did happen. Accident or arson? Texas heat upon dry grass or racially motivated? The first fire has no year associated with it, only acknowledgment. After the first fire there was a new building to be set, this time with six rooms to accommodate a continuation of the growing school. That would then burn down in 1935, be rebuilt, then burned down again in 1936. This is the final building that is standing today. This would also be the building that would be renamed T.B Harris, to honor the supporting professor. There would be several additions added to the school such as quote, “frame buildings were constructed to house the vocational and hot lunch programs. A south wing with a library, three classrooms, office and hall space was added in 1951-1960, a modern gym/auditorium was added east of the main building in 1962. The auditorium was the site of many community as well as school activities,” according to the Clio newspaper. The 50’s and 60’s is when the majority of the records will show the most history of the school, most likely due to the record keeping that wouldn’t be burned.

The school would continue to educate classes of black students, encouraging bigger things out of their student body then staying in the, at the time, small farming town of Belton. The ’60s paved new roads for black students as the Civil Rights movement grew across the country. Unfortunately despite the Brown vs Board of Education case officially “ending” public school segregation, this would be ignored by many Southern schools including T. B. Harris. It wasn’t until the Civil Rights Act of 1964, signed by Lyndon B. Johnson, that would “forbid racial discrimination in any activity or program that received financial support from the federal government, including public school systems. The act required the elimination of racial discrimination from classrooms, school-sponsored projects outside the classroom, services to pupils, educational facilities, hiring and assignment of faculty, and parents’ participation in certain school activities.” (Clio News)” March of 1966 N. L. Douglas, the at the time Belton School board superintendent, would notify all families with students within the school that the black junior high and high school were now being integrated, yet Harris would be turned into an elementary school. Although families with children first through sixth grade had their option when it came to the freedom of choice for elementary schools, only 75 children would be in attendance causing T. B. Harris School to officially close on Sept. 7 of 1966 then officially phased out on the 15th that November.

Despite its closing, the gym was still used for eighth grade sport events, it was the program area for special education, and more commonly used as office spaces. 1998 would be the year the building would be granted a Texas historical marker to commemorate the lasting legacy of the school with its impact on the students who graduated. In 2005, the school was given to the Belton School district where $900,000 was given to renovate the building for city usage. The building is now open to the public for events such as art exhibitions, meetings for community groups, and event facilities. This building stands as a staple within the community’s history, a reminder of how important education and equality is within our state, within our country, to everyone.

This school is such a tailored part of the history of Belton. Although segregated, there was a legacy created through the student body, an impact on the students, benefiting the individual students as well as the equality of rights. The most notable student from T. B. Harris was Reverend Roscoe Harrison Jr., an active member of the Belton community and a 1963 graduate from Belton’s segregated school.

After high school, he would go on to attend Temple College, Prairie View A&M, UMHB and then finally going to school for communications in Oklahoma. After his extensive schooling, he would go on to be the first black writer for the Temple Daily Telegram, San Antonio Express-News, and an editor for JET magazine, where he would be a member of JET Magazine’s Pulitzer Prize winning team that covered the assassination and funeral of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., along with being a Baptist pastor for 20 years within the community he grew up in, adding onto the legacy of furthering educational rights then continuing an advancing life of battling inequality. He was able to apply and graduate from those colleges because of his school opportunity. Reverend Roscoe walked across the many college campuses that he wouldn’t have the opportunity to if there wasn’t a high school diploma, although from a segregated school it still gave him hope and a successful future.

Another reported student was Mittie Russell who would graduate as valedictorian in the class of 1951. She would volunteer at the Bethel AME Church in Belton for 70 years, and worked in the Belton ISD food service department. Mrs. Russell would become a member of the Nolan Creek Lodge, keeping her school’s history alive by serving as the West Belton Ex-Students Association’s secretary. She was known well in her community, not allowing her past to affect her life.

“The importance of heritage is to give the younger students an idea of the things we endured,” said Billy Smitha, a 70-year-old class of 1952 graduate, stated in a news article interview during an alumni reunion. “That’s why it is so important — that way we never forget our history — because our parents attended the same school we graduated from and some of our children attended the school but did not finish there.”

The student legacy of T.B Harris lives on through the yearly reunions and the West Belton Ex-Students Association.

“The West Belton – T.B. Harris Ex Students Association was formed in 1982 to make sure and keep the legacy of the school alive with them. Their mission changed three years ago and changed their name to the West Belton – T.B. Harris Association. They realized that they not only wanted their association to be about the school they went to, but also the impact and importance of education. They also wanted to open their events to people not from West Belton or T.B. Harris so that other people could know about their school and its legacy,” reports the Belton Journal. The impact this school had made in its time of deeply racist beliefs then the impact it continues today as a celebration of education and equality as it is used for the whole of the Belton/Temple area.

Education should not be seen as a privilege or something to be withheld from a person, let alone a child who is trying to make their way in the world. African American children were denied their basic right as a citizen, as a human. It is in human nature to learn and grow ourselves, that should not be stripped from any child, in any country. The segregation period within America was a hard time that left thousands of people hurt, disregarded, and not seen as people. The school of T. B. Harris was a statement within the history of Belton, Texas.

The school is used for the community, seen as a place for everyone, not as a segregated, disrespected area. These residents of the town honor the history, encouraging the enrichment of children about its history and significance. The citizens of the town take time to remember how far our history has come, the legacy of what started off as a three-room schoolhouse.

In the rapid growth and the rush of day-to-day life we must take time to honor how resilient those students were, and how education is a natural right of man rather than an inconvenience to the ever advancing, technological world we continue to bloom into. T. B. Harris is hope within a once small schoolhouse, a generation of segregated children that were able to gain the basic right of education, continuing a legacy of battling inequality one lesson at a time.