Scripted illness

Live ‘patients’ help teach future doctors at Temple College

By Catherine Hosman

Photos by Nan Dickson

Macy Petru escorts “patient” Judy Riess into one of the examination rooms at the Clinical Simulation Center on the Temple College campus.

Riess has donned a hospital gown and sits on top of the examining table. She doesn’t feel well. She has had abdominal pain for two months, roller-coaster blood pressure and fatigue.

But Riess, 72, who is a retired nurse, isn’t really sick. She is one of several standardized patients (SPs) who act out a part to help third-year medical students pass their Objective Structured Clinical Evaluation (OSCE).

Petru, educator for the Standardized Patient Program with Baylor Scott & White, coaches Riess on her illness. “Hold your stomach, droop down some, move slowly. Your stomach hurts, it’s a dull pain.”

Petru steps aside when medical student Chad Smith walks into the room. He introduces himself to Riess before he begins the exam. “Is anyone else sick at home? Have you had a change in diet? Are there any bowel changes?” Smith asks.

Based on his observation and her presentation of illness, Smith continues to ask the same questions a doctor would in an attempt to point to a specific illness. After talking with her, he places a stethoscope to her heart and lungs. “Everything sounds good,” he says.

Lying back on the table he asks her to take a deep breath while he presses gently on her abdomen, feeling for anything unusual. He senses some tenderness. She reacts with a wince.

It’s hard to discern this teaching medical facility from an actual clinic or hospital. Each examination room and surgery suite is complete with the same equipment and tools one might find in a clinic or hospital setting.

Neil Coker, director of the Clinical Simulation Center, a partnership between Texas A&M University, Baylor Scott & White Medical Center–Temple and Temple College, says the Center has used standardized patients since it opened in 2004.

“(Student) activities from the medical school began almost immediately,” he says, “including exams done after clerkships—courses the medical students take their third and fourth year.”

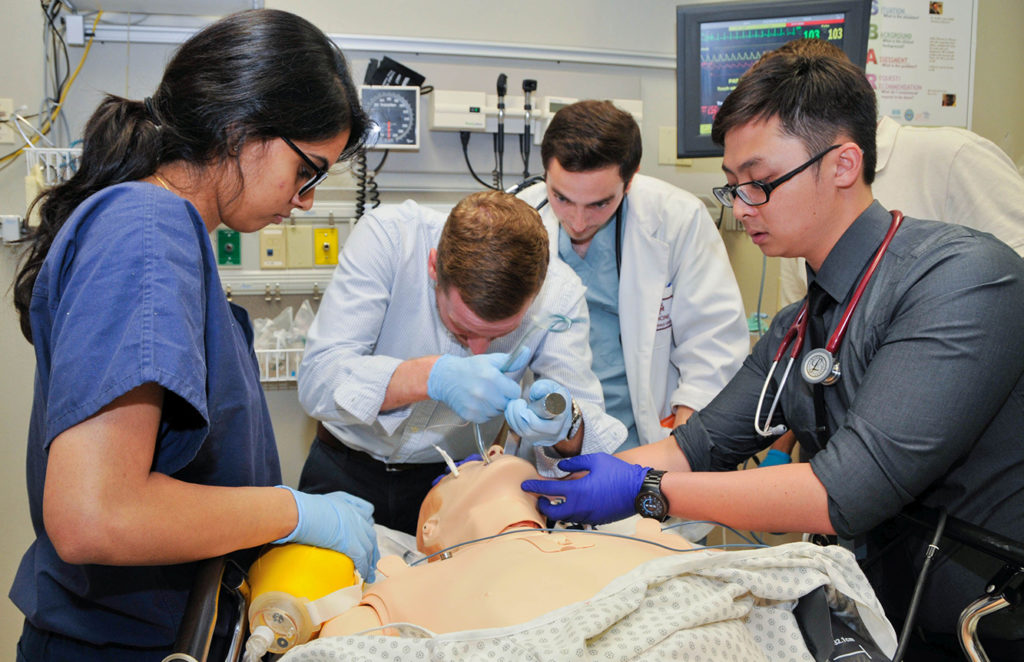

Student doctors get to practice on both mannequins and people. Coker says simulation with SPs assures medical students are able to see things and do things in a clinic environment with patients.

“Think of simulation as medical theater,” Coker explains. “Kim Alssup (clinical simulation coordinator) and I are the stage managers. We listen to what the faculty wants to see happen.”

Mannequins or people

Petru says their clinical simulation mannequins can do everything a human can do except roll out of bed and walk.

Coker adds that there are some things students need to see and be able to do that don’t always present themselves in mannequin simulations.

“A mannequin cannot express nonverbal pain,” Riess says, following her scripted performance. “A human can provide verbal feedback to enhance the learners’ communication skills, as well as show facial expressions.”

However, there are procedures that can be done on a mannequin that cannot be done on a person. For example, Petru says, “You cannot intubate Judy. But she can be a distraught family member.”

“And I have been,” chimes Riess.

In that scenario, Riess’ husband was coding out. “I was the distraught wife,” she says. “One student had to take me out of the room and bring me back in.”

Standardized patients come from all walks of life. They are retired physicians and people with medical experience (Riess is a retired psychiatric nurse).

“To be a strong SP, you have to have good memorization skills, be teachable, relatable, professional, punctual and reliable,” Riess says. “We are providing a service for future healthcare professionals.”

SPs also need to have a strong sense of confidentiality.

“We have to be able to keep things confidential,” Riess says. “We can’t talk about it in the community.”

Both simulation mannequins and standardized patients offer learning opportunities in whatever objective skills the learner (student) is trying to perfect, Petru says—with two exceptions: SPs offer learners an opportunity to work on a live patient and they are someone who can offer immediate feedback.

“A lot of things go into it. Judy, being a psyche nurse, is aware of what some of those illnesses look like. I can trust Judy based on her experience,” Petru says.

“SPs help medical students prep for their OSCE and Step II clinical skills test for their medical license to become a doctor,” adds Riess.

“The part of what everyone stresses to us is the safety of the patient and to do things in ways that maximize patient safety,” Coker says. “This ensures that every student sees every situation they need to see to become a competent, safe practitioner.”

A different kind of teacher

Petru is a Bell County native who grew up in Temple. Her desire to teach came to her early in life. She graduated college with a degree in elementary education from Texas State University in San Marcos.

“I felt a need to teach and educate,” she says. But she came from a family of nurses. Her mom and grandmother were nurses and her sister is currently a nurse.

“I didn’t go into elementary education, but I still wanted to go into education. I wanted to build relationships with people, grade them and teach them,” she says.

When the opportunity to become an educator for the Standardized Patient Program was presented, she didn’t hesitate.

“The job fell into my lap,” she says. “I am educating and training individuals within the community to consent to act a part of a medical condition. I also educate them to evaluate, learn and present their verbal feedback and written feedback as well (to the medical student performing the exam).”

Working with people and building relationships is natural to Petru. From age 16 to 26 she worked at H-E-B. “It was time I spent investing in the community,” she says. “I continued to work part-time while working at Scott & White. I started as a bagger and worked my way up to a lead position in the floral department.”

Today Petru shares her life with her husband, Anson, and their 3-year-old daughter, Kinsley.

“My husband and I showed pigs together in middle school with the Oenaville 4-H,” she says. “He lived in Troy and I lived in Temple.” Although they went their separate ways in high school, they were reunited in 2008 in Temple. The pair started hanging out, fell in love and married.

Pretending to be sick

There are different levels of standardized patients and they all require hands-on examination from student doctors, explains Petru.

“Level I is 90 percent of our SP pool. Actors present basic illness, like chest pain. Level II actors are classified as models. They allow student doctors to do things on their bodies,” she explains. “Performing a real exam is different on a human being than on mannequins.”

Petru and Riess have worked together for six years. Riess says she admires Petru’s ability to be friendly, but also her ability to “run a tight ship.”

“She keeps us SPs together. Because of her training and direction to us we are always where we are supposed to be when we are supposed to be there, and know what we are supposed to say and how we are supposed to act,” says Riess.