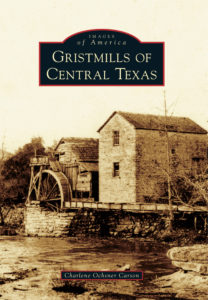

Gristmills of Central Texas

A conversation with Salado author Charlene Ochsner Carson

By CATHERINE HOSMAN

Drive through any back road country or town and historic markers seem to pop up all over. There are historic markers and landmarks in all 254 counties. Many of the early historical buildings these markers may refer to have disappeared, but there are still ruins of structures that once dotted the Texas landscape. Some of those early historical treasures are off the beaten path.

In her book, the “Gristmills of Central Texas,” Salado author Charlene Ochsner Carson takes us on a guided tour of gristmills from the missions of San Antonio to the Salado River in Bell County. She travels back in time along the rivers that fed the mills. She takes readers to the San Antonio, Guadalupe, Colorado, Brazos and Salado rivers. Black-and-white illustrations, some from her own collection, give the reader a look at the mills that once stood along the riverbanks.

In her book, the “Gristmills of Central Texas,” Salado author Charlene Ochsner Carson takes us on a guided tour of gristmills from the missions of San Antonio to the Salado River in Bell County. She travels back in time along the rivers that fed the mills. She takes readers to the San Antonio, Guadalupe, Colorado, Brazos and Salado rivers. Black-and-white illustrations, some from her own collection, give the reader a look at the mills that once stood along the riverbanks.

“The rivers of Texas were hosts to hundreds of gristmills,” she writes. “When settlers were looking for a mill site, they often looked at the springs and the streams that branched from the rivers. Springs usually provided a more reliable source or water, even in the dry times of summer.”

Most of the mills are gone now, but several have been purchased and turned into private homes or renovated to working condition and now stand as functioning landmarks of history.

Why did you decide to write about Gristmills?

I became interested in writing about gristmills when I learned that at one time the Salado River (as it was referred to in early writings) had eight working mills within nine miles of each other — more than any other river in Texas. Initially, I was going to just write about those eight mills, but I soon realized it would be impossible to get at least 200 photos of eight mills when most of them never had their photograph made in the first place. I knew then that I had to expand my topic so that is the reason I decided to research and write about the gristmills of Central Texas. Plus, with my farm-girl background it seemed like a natural topic.

How long did it take you to travel to all of these sites and collect information?

My husband, Maurice, and I spent about a year traveling the back roads of Texas searching for mills that we could photograph. Meanwhile, we also went to several libraries and other types of research centers looking for photographs of mills that we could use. When you publish with Arcadia, you need at least 200 photographs of the subject you are writing about. It was difficult to find that many photos of something that was in Texas in the 1800s before photography was in common use. We feel fortunate that we were able to find photos of the 54 different mills represented in the book.

Do you have a favorite gristmill?

As I worked on this project, each gristmill became my favorite. Even though a gristmill is an inanimate object, it has a personality. The John Teeter Mill at Homestead Heritage Village near Waco has a distinct personality and is an excellent example of the way all gristmills worked when they were working mills. Also, when you walk into the building, you are surrounded by the sounds and the smells of a working mill. Being at this mill gives you a sense of what it must have been like to visit a mill of the 1800s. My husband and I visited this mill in February 2015 and the miller gave us a thorough tour and explained how it worked.

Which gristmill seemed the most interesting to you?

I think the most interesting mill is the San Jose Mill at the San Jose Mission in San Antonio. It is also the most historic mill. Established in 1720, the San Jose Mill probably had more of an impact on people than any other mill established in Texas. The Indians who came to live within the walls of the mission did not realize that they were going to be driven to live in a more civilized way. Also, the work of setting up and running a mill was a foreign concept to them. The mill also changed the Indian inhabitants’ diet when orders were given to cultivate wheat in addition to corn. The native inhabitants had a difficult time adjusting to the new order of things.

Copies of Carson’s book are on sale at the Bell County Museum in Belton and at the Salado Museum.